Syrian rebels have freed prisoners — including toddlers — from a notorious, jam-packed prison dubbed the “human slaughterhouse,” where the Assad regime allegedly used an “iron press’’ to pulverize bodies.

The Saydnaya military prison just outside Damascus was emptied by insurgents over the weekend as the rebels took over the Syrian capital and forced dictator Bashar al-Assad to flee the country for Moscow.

Videos on social media showed haggard inmates in tattered clothes screaming in celebration when the rebel troops told them they were being freed from the infamous jail, where the Assad regime tortured and executed its political enemies.

“Don’t be afraid! … Bashar Assad has fallen! Why are you afraid?” said one of the rebels as he tried to rush the scores of inmates — including women with their young children — out of their tiny confines at the horrific site, called the “human slaughterhouse” by human rights groups.

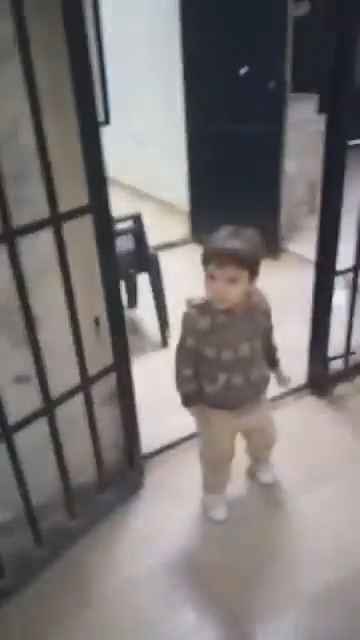

Disturbing images from the prison appeared to show a young child being held inside one of its underground cells, the Evening Standard reported, revealing the depths of the depravity of the Assad dynasty, which finally collapsed after more than five decades of rule.

Amnesty International and other groups have claimed that dozens of people were secretly executed every week in Saydnaya, estimating that up to 13,000 Syrians were killed between 2011 and 2016 alone.

An “iron press” that was allegedly used to crush prisoners at the facility was featured in unverified new videos shared by the rebels.

The large hydraulic press was reportedly used on prisoners’ bodies after they were hanged. Their bones would be crushed to powder, and there were containers below to collect their blood during the process, according to a Syrian journalist.

There also were reports of tens of thousands more prisoners who had yet to be freed because they were being held in hidden cells below the prison and hadn’t been found.

The Syrian civil defense group known as the White Helmets said in a statement it has deployed five “specialized emergency teams” to the prison, aided by a guide familiar with the site’s layout, to try to find any potential stashed-away prisoners, the BBC reported.

The Damascus Countryside Governorate publicly pleaded with former regime soldiers and prison guards to also provide the rebel forces with the codes to electronic underground doors.

The groups claim they have been unable to access the underground cells to free “more than 100,000 detainees who can be seen on CCTV monitors.”

The military prison was among a group of government jails where tens of thousands of prisoners were freed by rebel forces as the insurgents blitzed their way to the capital and overthrew Assad’s government in less than two weeks after 13 years of civil war.

Torture and secret executions were commonplace in Syria’s infamous prisons.

In 2013, a Syrian military defector known as “Caesar” smuggled out more than 53,000 photographs that showed clear evidence of rampant torture but also disease and starvation.

The prison system was used to house Assad’s political opponents — but also served to stoke fears among the Syrian people as they heard horror stories about the facilities, according to Lina Khatib, associate fellow in the Middle East and North Africa program at the London think tank Chatham House.

“Anxiety about being thrown in one of Assad’s notorious prisons created wide mistrust among Syrians,” Khatib said. “Assad nurtured this culture of fear to maintain control and crush political opposition.”

With the prisons’ doors now open wide, people have taken to the streets to search for loved ones they haven’t seen or heard from in years because they were jailed.

“This happiness will not be completed until I can see my son out of prison and know where he is,” said Bassam Masri. “I have been searching for him for two hours. He has been detained for 13 years.”

Many former inmates skipped the celebration and waited outside the prisons and at security branch centers, hoping their families would meet them there.

Heba, who only gave her first name while speaking to the AP, said she was looking for her brother and brother-in-law, who were detained while reporting a stolen car in 2011 and hadn’t been seen since.

“They took away so many of us,” said Heba, whose mother’s cousin also disappeared. “We know nothing about them … [The Assad government] burned our hearts.”

With Post wires