Last week social media platform X revealed the national origins of all its user accounts – divulging many top political voices on hot-button US issues are actually keyboard warriors based in Africa and Asia.

For many, such as fake Native American grievance accounts run from Bangladesh and Nigerians posing as Trump-loving Midwestern moms, their motivation is simple – trying to make money (usually from selling T-shirts).

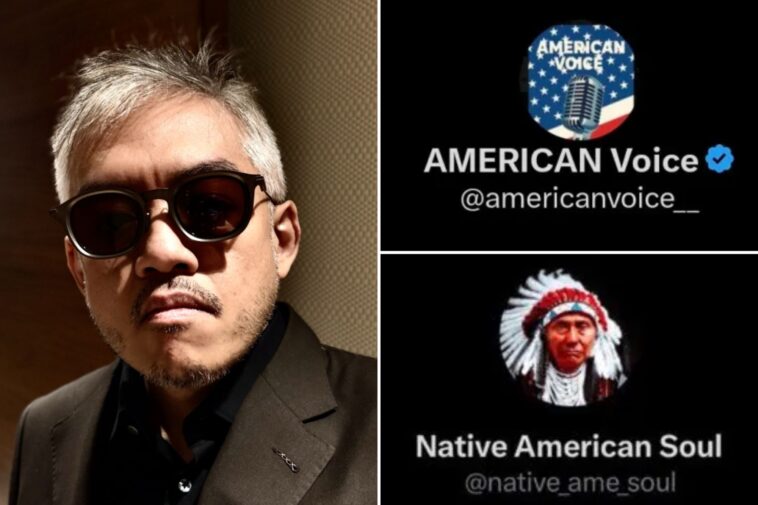

For others it’s more complicated, such as Ian Miles Cheong, a Malaysian-born, Dubai-based writer and X celebrity with 1.2 million followers.

He’s built his brand on acerbic social criticism and championing the new right in US politics, but says it was all on his followers for assuming he was actually in the country.

“The idea that you can’t have a say on anything regarding America just because you don’t live there is kind of silly because what happens in America happens everywhere else,” Cheong, 40, told The Post.

“On top of that, practically every country has a US military base at this point. It’s an empire, like it or not, and people are going to have opinions.”

Cheong became the target of attacks once it was revealed he is actually in Dubai.

“You’ve never set foot in America and yet you spend every day trying to influence our culture and politics. You talk about our country exclusively and never say a word about your own.

“If you don’t see why that might rub Americans the wrong way, I don’t know what to tell you,” one prominent American podcaster wrote to him.

Cheong notes his take is different to the army of “fan” accounts dedicated to members of the Trump administration — like Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt and Border Czar Tom Homan — which were exposed as operating out of India, Macedonia, and Thailand, alongside accounts from Africa with names like “MAGA Official” and “MAGA Scope.” Such accounts offer little beyond fawning endorsements and praise.

Their exposure helps US citizens make better choices as to who to listen to, according to personalities who are stateside.

“It takes away that mask and shows Americans exactly who’s speaking and gives you an opportunity to maybe identify what some ulterior motives might be,” Drew Allen, a California-based podcaster told The Post.

“Social media has leveled a playing field. It’s allowed people to have bigger voices and more influence and effectively work as journalists without being theoretically vetted by a news organization. And so with that, there’s a need for transparency about who these people are.

“But [a foreigner] can’t understand the body politic of America, our founding, and what we experience day-to-day in the same way I can or another American citizen can,” added Allen, who is writing a book about slain activist Charlie Kirk.

Cheong told The Post he agrees with many of his critics, saying foreign influence networks — such as Russia’s Internet Research Agency and China’s bot farms are a big problem.

“I do think they’ve been polluting the discourse and honestly I 100% agree. I think these people should not be able to influence anything,” he said.

The location exposure on X revealed two state-sponsored campaigns which weren’t widely known.

Scores of accounts pretending to be in the UK and advocating for Scottish independence all turned out to be based in Iran, while Chinese networks were meddling in the Philippines, trying to steer citizens away from the west and closer to China, according to Darren Linvill, a media forensics expert at Clemson University.

Linvill told The Post government-run interference is one side of the coin, but most of the accounts posing as something other than what they are on X are marketing operations run by single individuals either seeking profit or personal influence.

“What you’re seeing is capitalism at work. It’s the system that X built. These influencers are doing exactly what influencers who are actually located in the United States are doing and for all the same reasons,” Linvill said.

Bangladesh has, somewhat improbably, became a hub for Native American grievance politics, with at least half a dozen accounts with names like @NativeNationUSA and @Support_Natives found to be operating in the south Asian country.

Those accounts, with tens of thousands of followers collectively, shared Native American history factoids, memes calling America stolen land, and anti-Trump ephemera —while hawking $30 anti-colonialist T-shirts and $60 beaded shower curtains.

“It’s always T-shirts. If we got rid of T-shirt sales and cryptocurrency on social media you’d kill half the [problem],” Linvill said. “They’re just trying to connect with a particular audience in order to sell a product.”

Some accounts claiming to be real Natives became outraged by the revelation, blasting the foreign accounts for exploiting native “trauma” for profit and calling for X to ban those accounts.

Roughly two dozen African and Asian accounts pretending to be Americans were contacted by The Post but did not respond to requests for interview.

Linvill says the small amount of money X pays out to users for engagement can go a long way in a country like Bangladesh or Nigeria where the GDP per capita is $2,800 and $800, respectively, compared to $85,000 in the US.

For Allen, he recognizes the talent it takes to build a social media following and that people vote with their clicks.

“It can be a little bit frustrating, not because I’m jealous. I like to think that the cream rises to the top, and a lot of these people have earned their followings,” he said.