You learned right away just how charming he could be, how persuasive. Pete Rose extended his hand as soon as I knocked on the door of Room 1154 at the Essex House, a bright smile on his face, bedecked in a red sweater and a close-cropped haircut that looked straight from his 1965 baseball card.

“Mike, I loved the column you did on the Knicks yesterday,” was what he led with, and after a lifetime of being toasted (and later roasted) in the press, this was a man who knew well the fastest way to a columnist’s heart. “You think they have a successor lined up for Don Chaney?”

Of course, we weren’t inside this suite looking out on Central Park South to talk about Herb Williams, or Lenny Wilkens, or the Knicks. Rose had a new book out and he was on the pitch. “My Prison Without Bars” was disappearing rapidly from the shelves of the city’s book stores. In it, he finally ended a lie that by that afternoon at Essex House had reached its 15th year.

Sort of.

“You have to live with the cards that are dealt to you,” Rose said, an interesting metaphor given that the barless prison to which he referred was a result of a gambling addiction that until about 15 minutes earlier had deprived him of everything: his reputation, his place inside the game, and a place inside the Hall of Fame in Cooperstown.

“This book didn’t come out right now to try to persuade [then commissioner] Bud Selig to reinstate me.”

That, too, was a lie, of course. The final 35 years of Rose’s life were an endless barrage of jabs and jibes, admissions that were often as not incomplete. Thirty-five years Rose held a moistened finger in the air, trying to gauge the winds of public opinion. That sad journey ended Monday, when he died at 83.

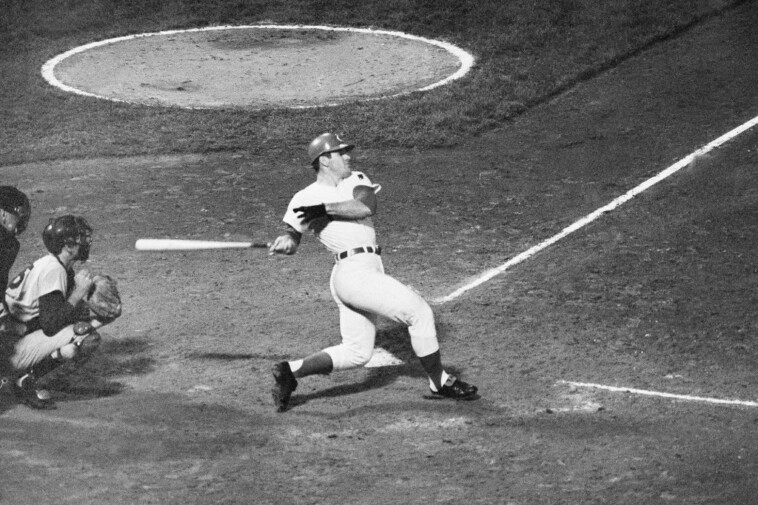

The numbers he left behind take your breath away when you study them: 4,256 hits, more than anyone who ever played the game, 67 more than Ty Cobb, the man Rose stalked incessantly until he passed him one magical night in Cincinnati, his hometown, on Sept. 11, 1985. That moment should be among the handful of forever snapshots in baseball history. He started crying, hugged his son, Petey. It was beautiful.

But by then he was also the manager of the Reds, brought home from exile in Montreal to set the record and maybe author a few more lines for his Hall of Fame plaque as a skipper. Except what we know — what the damning Dowd Report uncovered in excruciating detail — is that he’d already begun gambling. And in games involving his team.

The first play was deny, deny, deny, and all that did was stiffen baseball’s resistance, and the sport knew well how to hit him where it hurt most. Beginning with his first year of eligibility, Rose’s name never appeared on the Hall of Fame ballot issued to members of the Baseball Writers Association of America who’ve covered the sport for 10 years.

For years, friends and family and perfect strangers have asked: “Why didn’t you vote for Pete Rose for the Hall of Fame?”

The answer, all those times: I never had the chance. Baseball never allowed us a vote.

By 2004, Rose went the other way. He admitted what he did.

“I’m not trying to justify what I did because I was wrong,” Rose said that day at the Essex House. “I wish I’d paid greater attention to Paul Hornung and Alex Karras [both suspended by the NFL for the 1963 season because they’d admitted to gambling]. Maybe that was the problem, that they only got a year’s suspension.”

Keep up with the most important sports news

Sign up for Starting Lineup for the biggest stories.

Thanks for signing up

As the years passed, baseball never wavered, even as the sport jumped with both feet into bed with every gambling house imaginable, never acceding to how hypocritical that seems. Rose never stopped pitching, showing up every summer in Cooperstown to sign memorabilia the week of Hall of Fame induction — a ghostly, ghastly fate.

Still, there was always a sense that Rose was never quite willing to come completely clean. He could be awfully convincing though, always smooth. As we shook hands goodbye that afternoon on Central Park South 20 years ago, he asked me, “Let me ask you something, Mike. If you could vote for me, would you vote for me?”

I asked him, “Let me ask you something, Pete. Did you bet on baseball as a player?”

He laughed. This is what he said:

“I’ll take that as a yes!”

This is what he didn’t say: “I never bet on baseball as a player.”