New York filmmaker Hilan Warshaw had no intention of beginning his documentary on Henry Morgenthau with darkness.

But after the Oct. 7 terrorist attacks in Israel last year, he felt he needed to make a statement about antisemitism — the same hate which dogged his subject, the former secretary of the Treasury during the Second World War.

“Honorable Mr. Morgenthau,” which premieres at the Quad Cinema Sept.13, plunges the viewer into several uncomfortable minutes of darkness, punctuated by angry snippets of audio from protesters screaming epithets like “Zionists need to die” — a refrain Warshaw heard often during pro-Palestinian protests in New York City earlier this year.

“When I started making this film, I was determined not to put anything modern-day into it,” Warshaw said in an interview with The Post.

“I wanted to tell the historical story as immersively as possible, without making contemporary parallels. But after October 7, I found the subject of my film facing me in the world we live in.”

In his Upper West Side neighborhood, posters of Israeli hostages, some of babies and toddlers, were defaced with swastikas or torn down, he said.

“Anyone who’s intellectually honest has to ask: What on earth is behind the ferocity of these protests,” said Warshaw, an Emmy Award-winning writer and director whose previous films include “Wagner’s Jews,” which chronicles the Jewish supporters and fans of controversial German opera composer Richard Wagner.

“Antisemitism, the tradition of scapegoating and hating the Jewish people … has been deep-seated in Western society and beyond for more than 2,000 years,” Warshaw said. “And it hasn’t gone anywhere.”

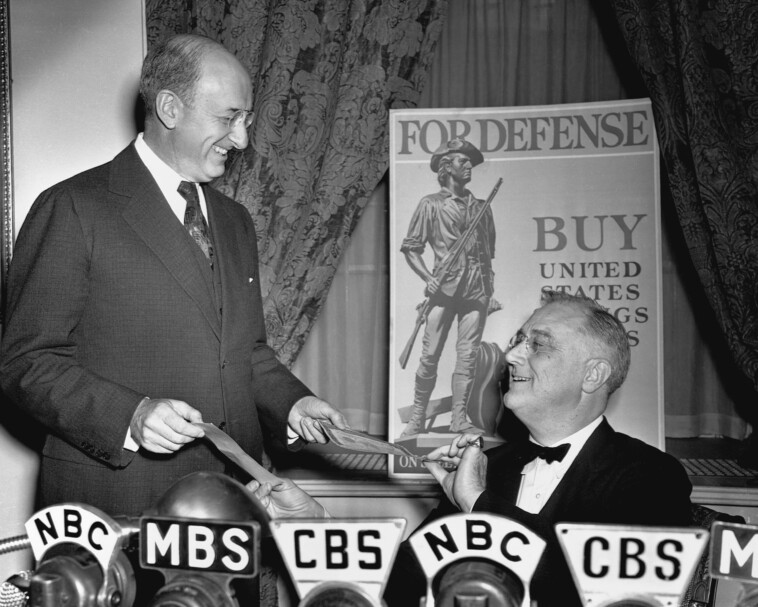

Antisemitism pervaded the upper echelons of the wartime government of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, where Morgenthau, a longtime friend of the president’s, grew increasingly frustrated at his inability to save Europe’s Jews from Nazi concentration camps.

The film begins with the heartbreaking letters sent to Morgenthau from distant relatives in Germany, begging him to bring them to America. Morgenthau’s father, a real estate developer and ambassador to the Ottoman Empire during the First World War, was born in Germany, and immigrated with his family to New York City in 1866.

He created a dynasty, and while Morgenthau Sr. was well known as a leader of Reform Judaism in the city, the second generation of the Morgenthau clan was hardly made up of practicing Jews.

If anything, they were fiercely American, a storied family of intellectuals and public servants who liked to spend most of their time on a farm in upstate New York near the Roosevelts’ country estate.

The Morgenthaus celebrated Christmas every year at their Dutchess County retreat, and Morgenthau confessed that he had never been to a Passover seder until after he left government employ at the end of the Second World War.

“Being Jewish was something that was never discussed in front of children,” says his son Henry Morgenthau III in the film. “It was kind of a birth defect.”

As a child, when Henry Morgenthau III was asked by a little girl in Central Park what his religion was, he asked his mother, who said that if anyone asked him again, he should just reply that “you’re an American.”

Henry Morgenthau III, an author and producer, died in 2018. His younger brother, Robert, was Manhattan’s longtime district attorney, who died a year later. Their younger sister, Joan Morgenthau, a doctor, died in 2012.

Henry Morgenthau, born in 1891, was the quintessential American country gentleman and bureaucrat, who was fiercely loyal to Roosevelt. He attended Phillips Exeter Academy and the Dwight School before going on to study agriculture and architecture at Cornell University.

Although he never earned an academic diploma, he helped Roosevelt design the New Deal, and prepared the US economy for war as secretary of the Treasury, the second-highest-ranking cabinet seat.

But when it came to rescuing Jews, his efforts were stymied. Assistant Secretary of State Breckinridge Long, who oversaw the agency’s Visa Division, prioritized US national security over humanitarian aid, and was also a known antisemite.

A popular propaganda film, “Confessions of a Nazi Spy,” fed into the wartime hysteria that helping refugees would allow spies to penetrate the US.

“There were many obstacles to rescue,” said Warshaw. “The State Department was filled with antisemites and popular opinion was opposed to letting in refugees.

“The sad fact is that Roosevelt didn’t take action to save more Jews because he didn’t believe in doing so. He once boasted to Morgenthau that he was personally responsible for Harvard’s instituting a quota on Jewish students.”

In 1942, when secret cables indicated the Nazis were killing more than 6,000 Jews a day in Poland, Morgenthau began working with the World Jewish Congress and other relief groups to help rescue Jews in Europe.

In 1944, he persuaded Roosevelt to create the War Refugee Board, which sponsored Swedish businessman Raoul Wallenberg’s mission to Hungary to help Jews leave the country. More than 200,000 Jews were saved.

Despite his efforts, Morgenthau was treated with contempt by his government colleagues, especially after Roosevelt’s death in April 1945. Roosevelt’s successor, President Harry Truman, refused to send any of Roosevelt’s advisers — a group that included Morgenthau and aides whom Truman called “the Jew boys” — to the Potsdam Conference where the US, Great Britain and the Soviet Union hammered out the future of Germany.

For his part, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill referred to Morgenthau as “Shylock.”

Despite the opposition, Morgenthau pushed forward even after he left government. He plunged into relief work for Jewish nonprofits with the help of his longtime secretary, Henrietta Klotz, a Jew and one of the heroes of the film, who was unrelenting in her mission to save refugees.

“When push came to shove, he was confronted with horrible knowledge, not only about the Nazis but about his own government,” said Warshaw of the subject of his film.

“Unlike virtually anyone else in his circle, he defied the advice of his family, the orders of the president, and … put everything on the line to fight for what was right.”

In his later life, Morgenthau donated his energies to Jewish philanthropic efforts and was a financial adviser to Israel. He died of heart failure in 1967.

“Honorable Mr. Morgenthau” premieres at Quad Cinema on September 13 and continues through September 19. Filmmaker Hilan Warshaw will answer questions after the screening on September 14 and 15.