French satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo is set to publish a special God-mocking edition next week to mark 10 years since an attack on its offices by jihadist gunmen that left eight staff members dead.

The anniversary of the shocking attack on freedom of expression is being used by the atheist publication to send a message of defiance to the extremists who burst into its offices on January 7, 2015, then fled shouting they had “killed Charlie Hebdo”.

“They didn’t kill Charlie Hebdo,” editor-in-chief Gerard Biard told AFP in a recent interview, adding that “we want it to last for a thousand years.”

The attack by two Paris-born brothers was revenge for Charlie Hebdo’s decision to repeatedly publish caricatures lampooning the Prophet Mohammed, Islam’s most revered figure.

The massacre of some of France’s most famous cartoonists signaled the start of a gruesome series of Al-Qaeda and Islamic State plots that claimed hundreds of lives in France and Western Europe over the following years.

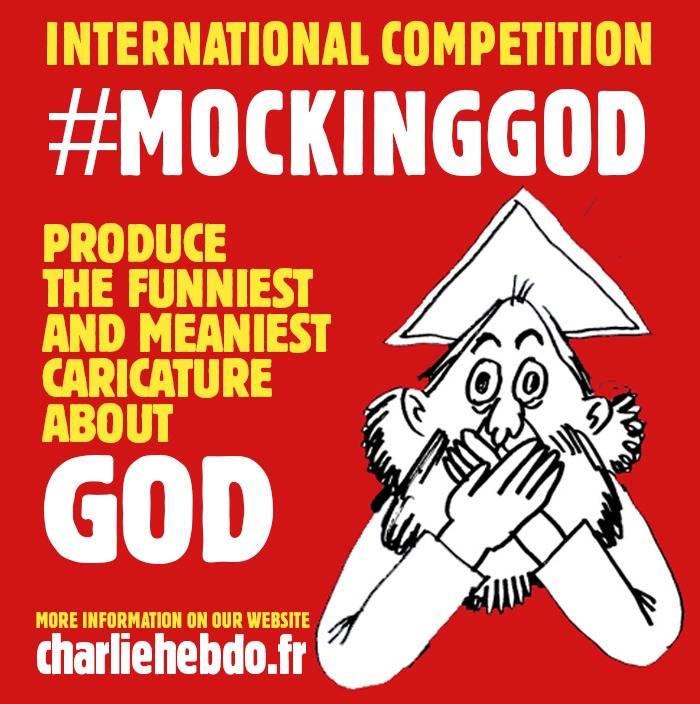

Next week’s edition is set to feature the results of a typically provocative competition launched in November to draw the “funniest and meanest” depictions of God.

It will be revealed on Sunday evening.

It is intended for “everyone who is fed up with living in a society directed by God and religion. Everyone who is fed up with the so-called good and evil. Everyone who is fed up with religious leaders dictating our lives”.

President Emmanuel Macron and Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo will attend commemoration events on Tuesday at the location of the attack, as well as that of a separate but linked assault on a Jewish supermarket.

The Charlie Hebdo killings profoundly shocked France.

The attack fuelled an outpouring of sympathy expressed in a wave of “Je Suis Charlie” (“I Am Charlie”) solidarity with its lost contributors including famed cartoonists Cabu, Charb, Honore, Tignous, and Wolinski.

But it also led to questioning and in some cases a furious backlash against Charlie’s deliberately offensive, often crude strain of humor, part of a longstanding French tradition of caricaturing.

Since its founding in 1970, it has regularly tested the boundaries of French hate-speech laws, which offer protection to minorities but allow for blasphemy and the mockery of religion.

Free-speech defenders in France see the ability to criticize and ridicule religion as a fundamental right acquired through centuries of struggle to escape the influence of the Catholic Church.

Critics say the weekly publication sometimes crosses the line into Islamophobia, pointing to some of the Prophet Mohammed caricatures published in the past that appeared to associate Islam with terrorism.

“The idea is not to publish anything, it’s to publish everything that makes people doubt, brings them to reflect, to ask questions, to not end up closed in by ideology,” director Riss, who survived the 2015 attack, told Le Monde in November.

“Basically, not being screwed over by what’s fashionable.”

The attack on Charlie Hebdo brought a mostly marginal publication into the mainstream, as well as propelling it to the attention of hundreds of millions worldwide who often struggled to understand its contents.

More than three million people marched in solidarity in the streets of France afterward, and around 40 world leaders flew into Paris to make a statement in defense of the free press.

A special post-attack edition of the newspaper sold more than eight million copies and donations poured in, giving the publication a financial windfall at odds with its anarcho-leftist spirit.

Subscriptions ballooned to more than 200,000 but have now fallen back to around 30,000, with another 20,000 copies sold at newsstands and in shops each week — more than their sales at the time of the attack.

Thanks to new recruits, around 12 cartoonists are back working on the magazine at a secret, heavily protected office.

Controversy is never far away

A front-page depiction of the Virgin Mary in August suffering from the mpox virus led to two legal complaints from Catholic organizations in France.

A cartoon by Riss in 2016 that linked a child refugee found dead on a beach in Turkey to foreign sexual attackers in Germany caused outrage, as did another the year after poking fun at First Lady Brigitte Macron’s age by showing her pregnant.

On the first anniversary of the attack in 2015, Charlie Hebdo published a front-page cartoon of a bearded God-like figure carrying a Kalashnikov rifle.

“One year after, the killer is still on the run,” read the title.